Posted on The History Blog in 2012, but still SO COOL, from both type and history perspectives.

Third original Fahrenheit thermometer surfaces

An original mercury thermometer made by Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, inventor of the mercury thermometer and creator of the temperature scale that bears his name, is going up for sale at Christie’s Travel, Science and Natural History sale in London on October 9th. This is only the third Fahrenheit thermometer known to exist today. The other two, one from 1718 and a later one from 1727, are in the Museum Boerhaave in Leiden.

Until the anonymous private collector consigned his for sale at Christie’s, the two in the museum were the only ones known to exist. The collector has had the thermometer since the 1970s but never published it or exhibited it. An original Fahrenheit mercury thermometer, the only known one in private hands, coming up for sale is therefore an immense deal. The estimated sale price is £70,000 ($112,000) to £100,000 ($160,000), but the sky’s the limit for such a rare piece.

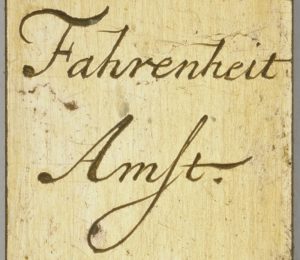

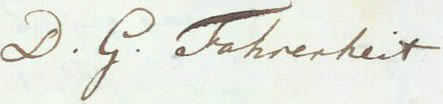

The brass instrument is marked on both sides of the glass tube from 0 to 132 degrees Fahrenheit. The mercury and glass tube have been replaced, but the thermometer was deliberately made for those parts to be replaced when necessary. On the back is the greatest prize of them all: an inscription of “Fahrenheit Amst,” his signature and the place where the thermometer was made, i.e., Amsterdam. It actually looks like his autograph, too. It’s not just printed or engraved in generic font. Compare it to the signature on this May 7th, 1736 letter to Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish naturalist who invented the binomial system of taxonomy we still use today to identify plants and animals.

Fahrenheit’s interest in scientific instruments began when he was a teenaged orphan/juvenile delinquent. Born in Danzig, now Gdansk in Poland, in 1686 to a wealthy German Hanse merchant, Fahrenheit was orphaned at 15 when his parents died from eating poisonous mushrooms. Although his father had intended he would go to university and study medicine, after his parents’ death in 1701 the city-appointed guardians of the Fahrenheit children (Daniel was the eldest of five siblings) decided he should follow in his father’s footsteps instead and keep the family business going. Daniel was an excellent student with a particular interest in science; he had zero desire to get into sales. In 1702 he was apprenticed against his will to Herman Van Beuningen of the prominent Dutch merchant family and sent to Amsterdam to learn bookkeeping and the mercantile trade.

It was during his apprenticeship that he first encountered Florentine thermometers. Invented in mid-1600s Florence by a private academy of scientists, many of them former students of Galileo, under the sponsorship and active support of Ferdinando II de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, these sealed glass tubes with bulbs of wine spirits at the base were the first temperature sensors that were not also barometers affected by air pressure. They were in great demand across Europe, which is how Fahrenheit came across them in the course of learning the business.

According to a letter his guardians sent to the Mayor of Danzig four years later, Daniel got into trouble as soon as he stepped foot in Amsterdam, eventually stealing money and repeatedly running away, not to mention indulging in behaviors of such a foul nature they could not stand to describe them. According to later biographers, Fahrenheit managed to get through four years of his apprenticeship, but was already making meteorological instruments by the last years. The money his guardians claimed he stole he in fact appears to have borrowed to fund his experiments in thermometer-making. When he couldn’t repay the debt, his guardians were forced to pay it out of his inheritance.

Sick of dealing with him, his guardians decided to send him overseas with the Dutch East India Company. In 1706, they wrote to the Mayor of Danzig asking the city council to authorize a warrant for Daniel Fahrenheit’s arrest and deportation to the East Indies. In January of 1707, the Mayor complied.

Now 20 years old and with a warrant hanging over his head, Daniel moved around constantly, traveling through Germany, Sweden and Denmark, far out of reach of the authorities. In 1708, he visited Danish astronomer Ole Roemer in Copenhagen. In addition to being the first astronomer to determine the speed of light, Roemer had also worked on thermometers and devised a temperature scale of his own. The Florentine thermometers used widely varying scales. The lowest point was the coldest day in Florence during the year a given instrument was manufactured; the highest point was on the hottest day. Roemer created a fixed-point scale of 60 degrees — freezing brine was 0, boiling water was 60 — and because water froze 1/8th of the way down, divided it into eight parts of 7.5 degrees each.

Sometime after this visit, the warrant for Fahrenheit’s arrest was withdrawn. It’s possible Roemer had a hand in this, since he was not only a figure of great importance in the scientific community but also Copenhagen’s chief of the police. Fahrenheit continued his peripatetic wanderings and his experiments. His aim was to create a thermometer that was easier to manufacture, easy to calibrate and more reliable. He learned how to blow glass so he could make his own capillaries.

Fahrenheit was inspired by Roemer’s scale to create one of his own that was less awkwardly sectioned and with three fixed calibration points: freezing brine, freezing water and “blood heat” or body temperature. He chose to use a factor of eight rather than Roemer’s 7.5, then divided each degree into four. Multiply eight by four and you get 32. That random happenstance is how the freezing point on the Fahrenheit scale wound up being 32 degrees.

His early thermometers used wine-spirits like everyone else’s. In 1714, he managed to produce two thermometers that produced nearly identical results despite their different ranges. This was a major breakthrough. That same year he had another breakthrough when he replaced the alcohol with mercury. Quick-silver, as it was then called, expands and contracts more evenly than alcohol. It is also accurate at a wider range, allowing temperatures to be taken considerably below the freezing brine point and considerably above the boiling water point. Fahrenheit’s mercury thermometer could accurately record lower and higher temperatures and with far more fine gradations between.

You can see that on the scale of the newly-revealed thermometer which is just bristling with degree marks. There is no date on that thermometer, so we don’t know exactly when he made it. Fahrenheit published his new temperature scale in 1724, but he began to produce mercury thermometers when he settled down at his workshop in Amsterdam in 1717. He kept producing them until his sudden death from a fever during a trip to The Hague in 1736.

He was buried in a pauper’s grave in the cemetery of Kloosterkerk (Cloister Church). A commemorative plaque was installed in the church in 2002.