A fascinating article about calligraphy for the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, in the waning days of hand-lettered books, from Noor Al-Samarrai at Atlas Obscura.

See a Dazzling, Exuberant Renaissance Calligraphy Guide

A masterclass in script, illuminated with an array of curiosities.

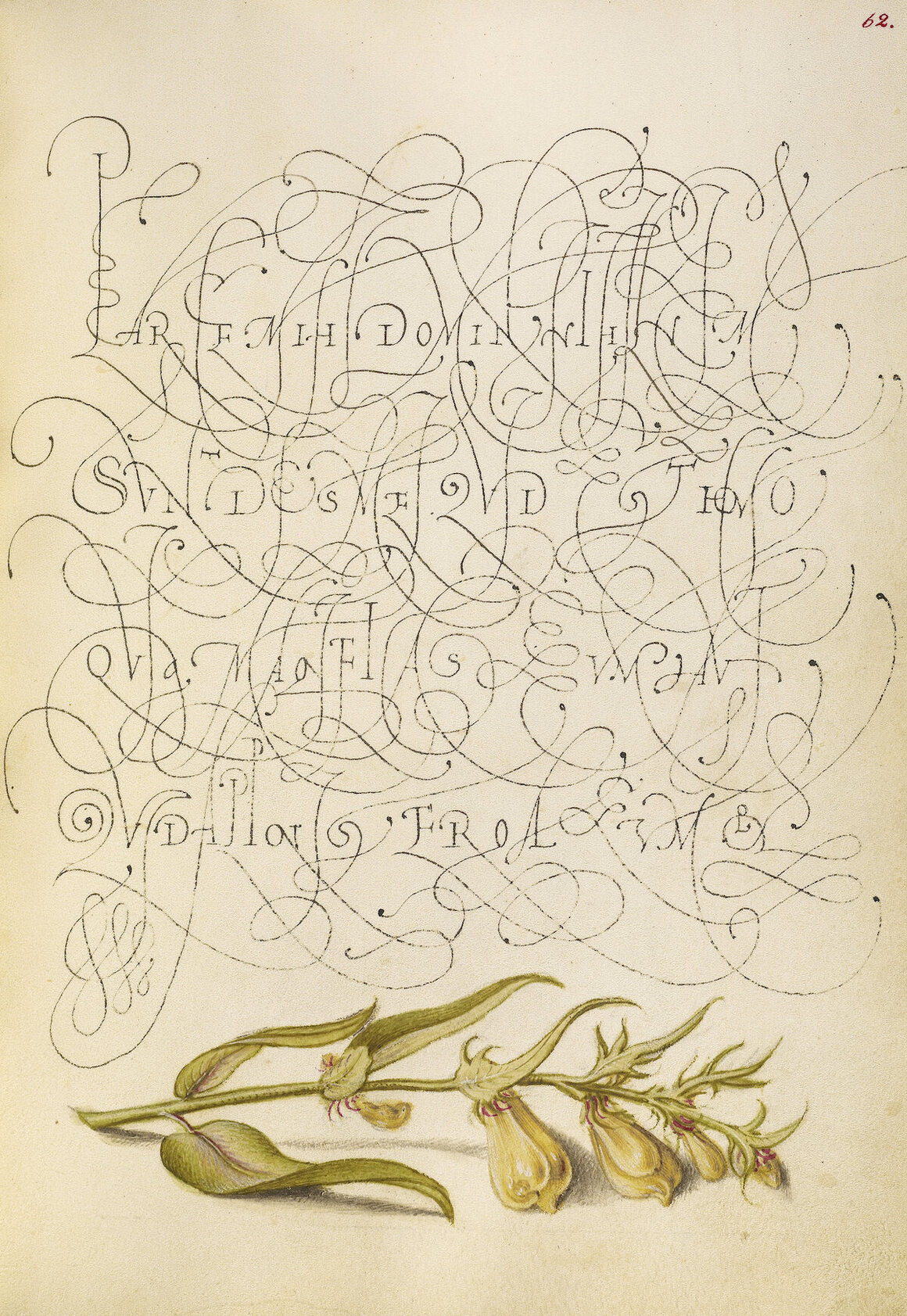

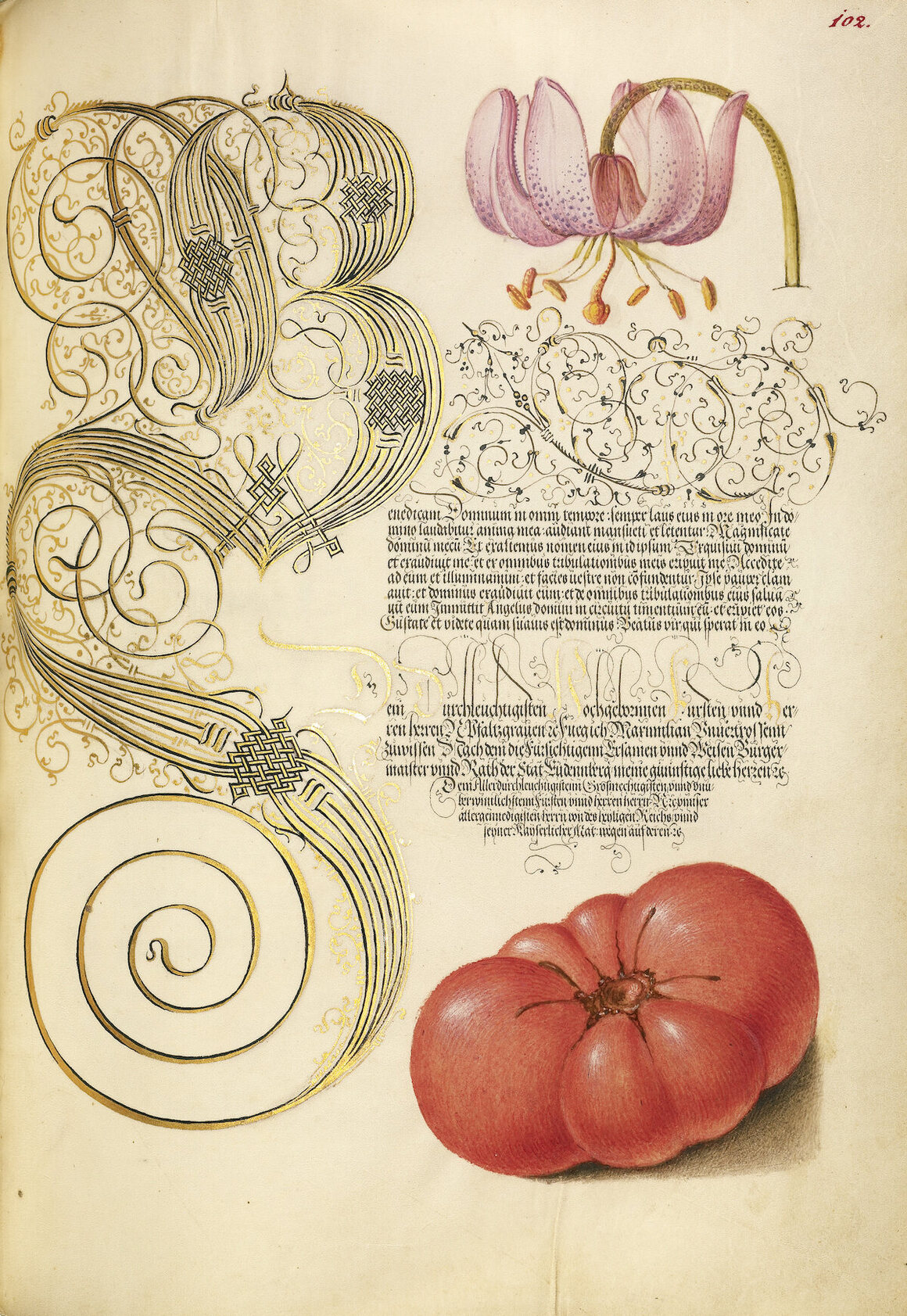

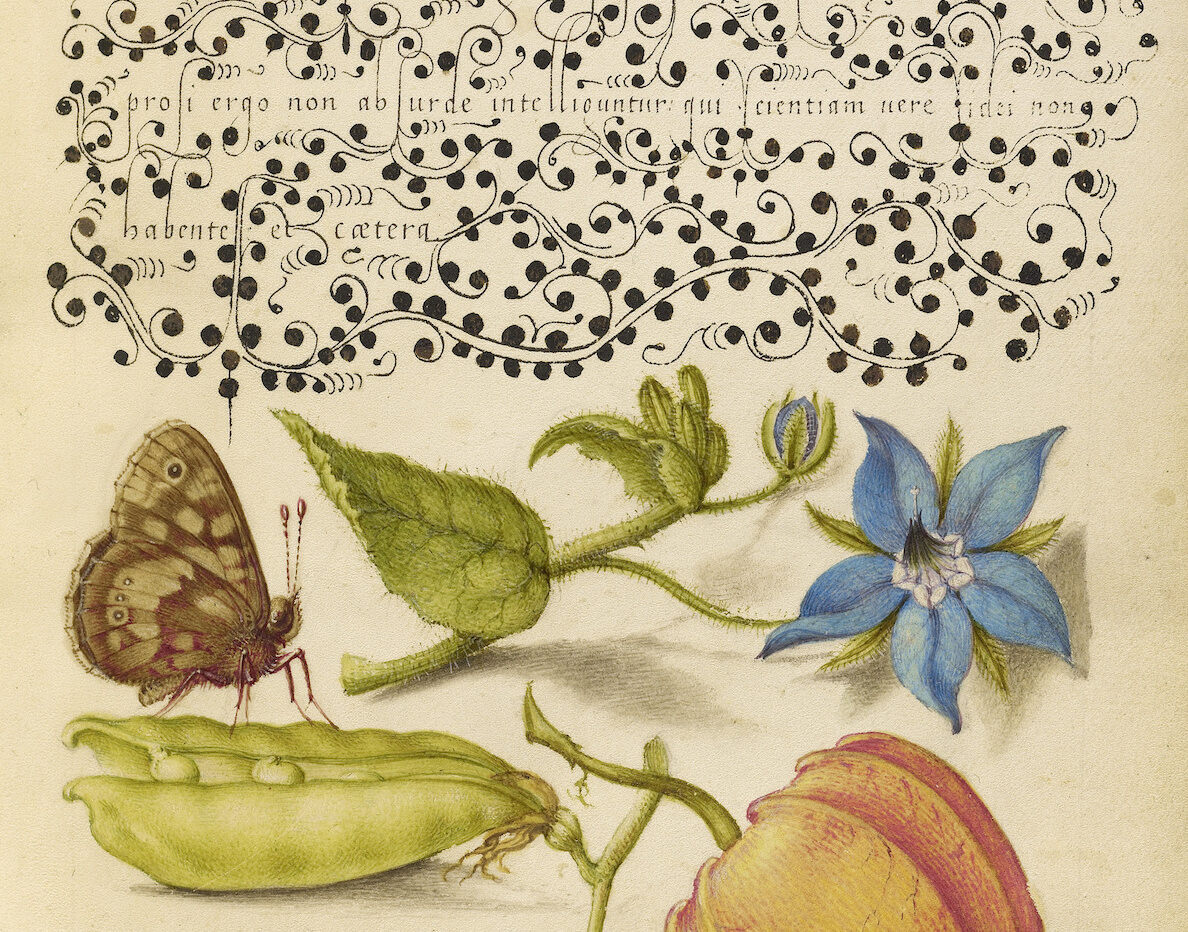

Georg Bocksay, then secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I in Vienna, composed the manuscript over the course of 1561 and 1562. Commissioned as a calligraphy manual, it was more like a catalogue of Bocksay’s unparalleled penmanship. A century before, the printing press had overtaken the handwritten manuscript, and transformed the trade skills of lettering and illumination into something more akin to art forms. Rather than instruction, the manuscript provides a bombastic display of Bocksay’s skill, and showcases the artisan talent that the emperor was able to attract. “It’s kind of in the stratosphere,” says Elizabeth Morrison, a specialist in Flemish illumination at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, where the manuscript is housed.

Most of the actual text of Mira calligraphae monumenta is taken from the Bible—the “lorem ipsum” graphic filler used in those times. The dizzying circular text on a page featuring a pair of pears and a seashell is actually the Lord’s Prayer squeezed into an area the size of a quarter, dexterously rendered with a bird-quill pen and runny ink. Bocksay used the same tools as other scribes of his day, but he had the advantage of experience. Having been born into a noble family in Croatia, he learned to read and write at an early age. This allowed him to develop his calligraphic skill so much that he could support himself and his family on it. Even as handwritten books were going out of fashion, elites such as emperors still had the appetite—and budget—for them.

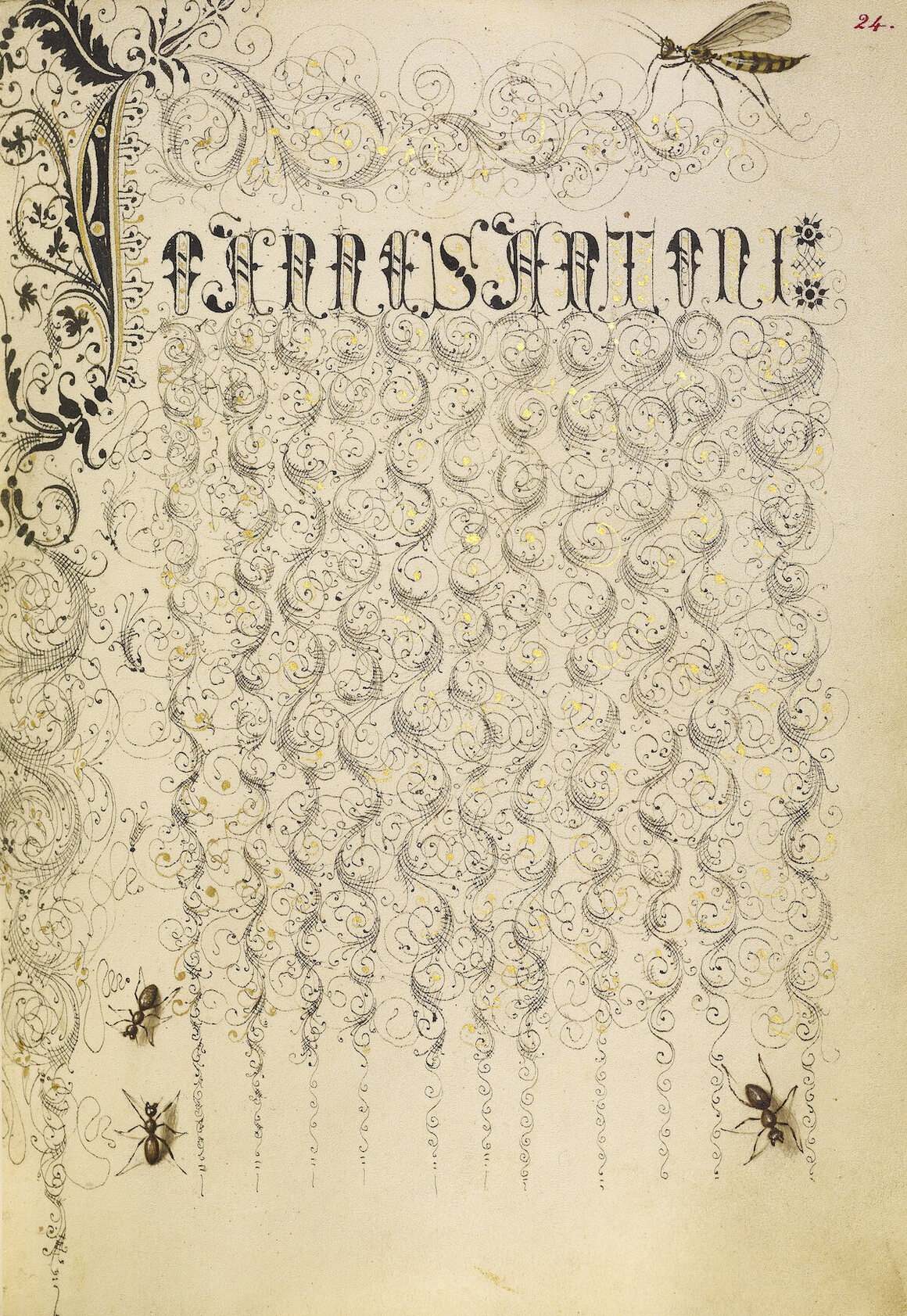

It was common for a manuscript’s text and illuminations to be created by different artists. Bocksay had left room for illuminations around his pyrotechnic displays of penmanship. But the image of familiar flowers, delectable fruit, and animals from the Americas were not created during Bocksay’s life, but 15 years after his death. Their artist, Joris Hoefnagel, was hired by Emperor Rudolph II, Ferdinand’s grandson. Although the Flemish Hoefnagel never knew his Croatian counterpart Bocksay, he responded to the inscriptions with a matching degree of deftness and play. On a page where the text is adorned with curling shoots studded with black dots, Hoefnagel echoed the style with a drawing of pea pods. On another, trompe l’oeil ants crawl among the feathery, gilt tendrils of Bocksay’s work.

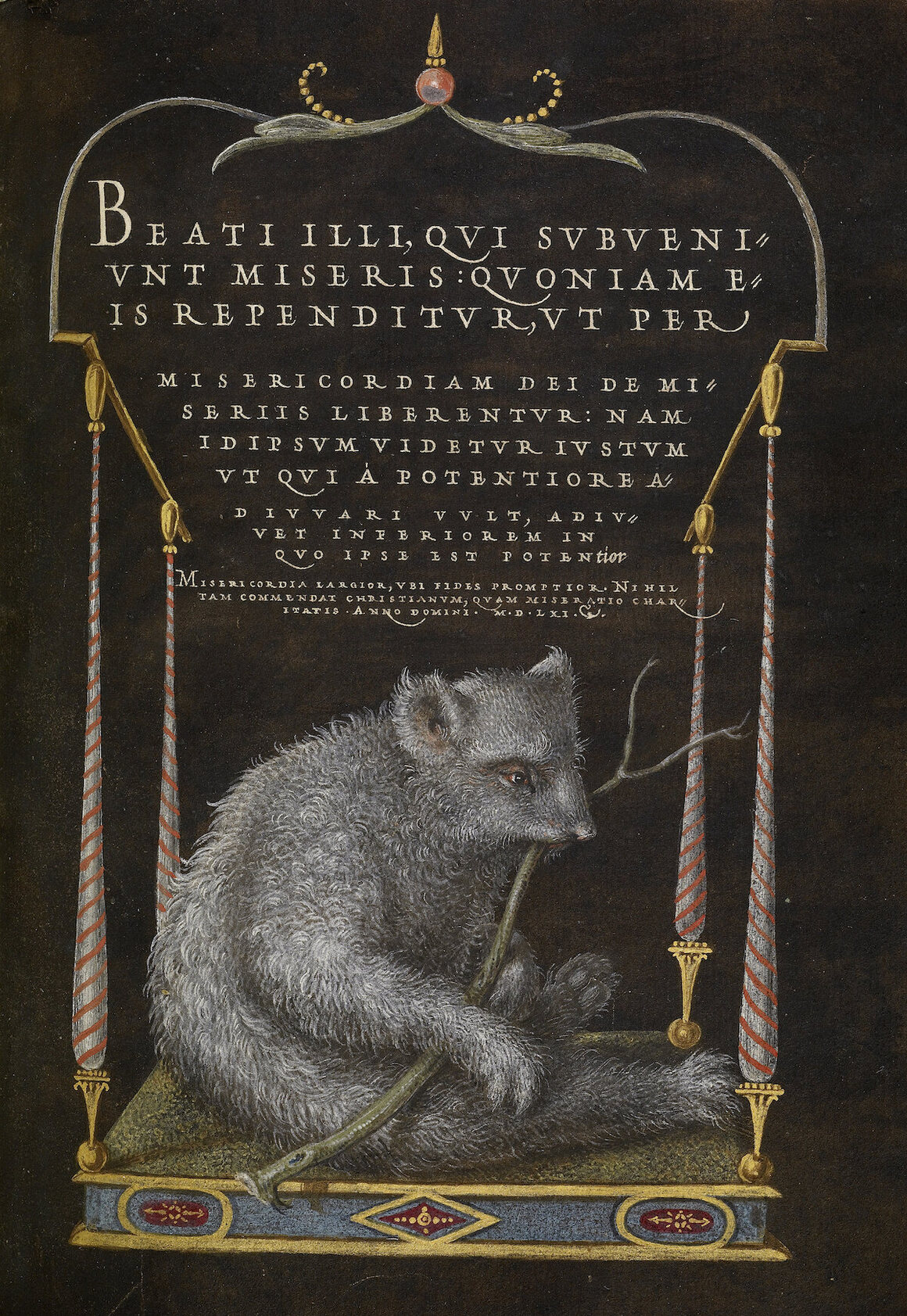

Some pages—unusually for this time period—had solid black backgrounds. For these, Boshkay used a resist technique, in which he lettered with a substance such as beeswax that would repel the black used to coat the rest of the page. Conservators have not yet identified the blacking substance, but it may have been ash.

On one of these black pages—there are six in the 184-page manuscript—Hoefnagel drew a sloth, an example of the New World life the emperor was attracted to. Rudolph II had moved from Vienna to seclusion in a castle in Prague. For his Kunst-und-Wunderkammer—a cabinet of curiosities and wonder—he sourced specimens that had never before seen in Europe. Accounting records of compensation doled out to survivors of attacks and families of fatalities confirm that he kept a live lion and tiger, who roamed around his castle.

Pages from Mira calligraphae monumenta are on view at the Getty Museum until April 7, 2019, and again from May through August. Atlas Obscura has a selection of pages from the manuscript.