Incredible maps take on subterranean London, Thomas More’s 1516 book Utopia.

By Olivia Solon from wired.co.uk:

Artist Stephen Walter has a solo exhibition [in London] showcasing his intricate hand-drawn maps, including two of London and one that revisits Thomas More’s fictional island state of Utopia.

In addition to cartography, Walker has created a series of landscapes often peppered with visual and textual information, including symbols and logos—traffic signs, tourist signs, and even religious iconography. Around a third of the show—called Anthropocene—will be made up of landscapes, while roughly two thirds of the show will be maps.

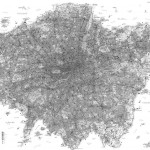

One of Walter’s most attention-grabbing pieces has been The Island—a piece that satirizes London-centricity, showing the capital and its commuter towns as independent from the rest of the country. The highly-detailed map features a wealth of information, symbols, and personal information. For example, in Westminster you will find “squirrel feeders,” “men in silly hats” along the Mall, and the “seat of power” at Downing Street, along with a hazard symbol.

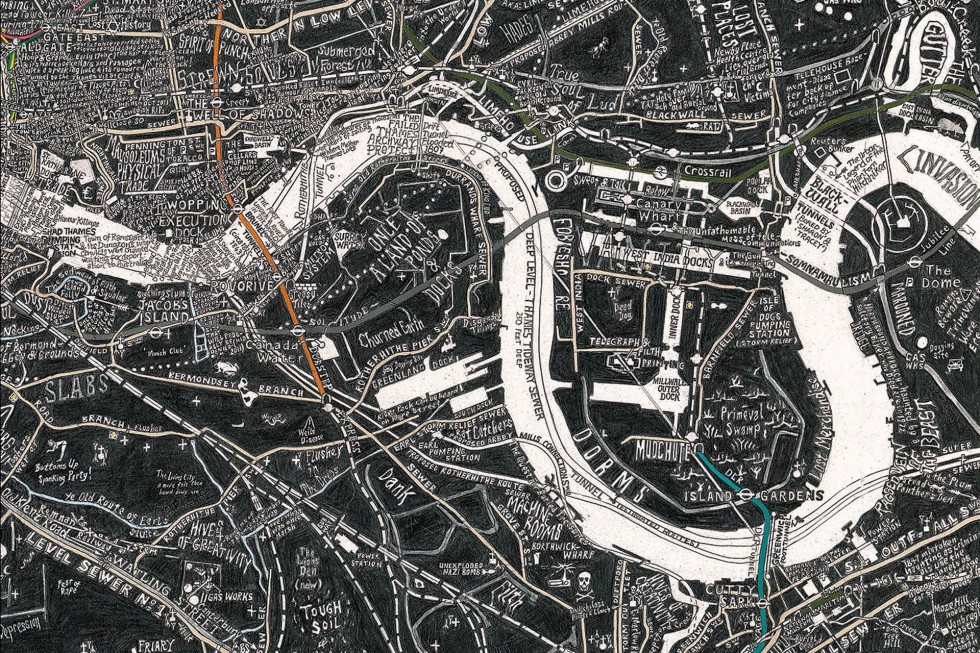

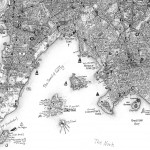

Similarly, London Subterranea, commissioned by the London Transport Museum, shows what lies beneath the ground of the capital. From tube lines, sewers, and gas pipes to bunkers, burial sites, ley lines, and governmental tunnels.

New Utopia sees Walter reimagine the island of Utopia first described in Thomas More’s book from 1516. It was originally described as a prosperous and egalitarian island republic. Walter uses Abraham Ortelius’s 1596 map as a template, but shows the island decades after a capitalist revolution has transformed its society, turning the place into a “leisure island” for those who go there.

Detail from London Subterranea

Detail from London Subterranea

Click on images above and below for larger versions.

A total of 55 pieces will be shown in three rooms: one dedicated to the maps, one to landscapes, and a third looking at believability.

Walter told Wired.co.uk that he’s always been interested in using signs and symbols to produce images and tell stories. “My drive for storytelling has to work hard to find itself spoken through this filter of public language and shared concerns and inherited history. Maps are a collection of these signs and symbols.”

His pieces tend to focus on places that he really cares about, “otherwise it’s just sheer illustration.”

Once he’s decided on a place and a size of the piece, he immerses himself in reading and exploring to get “all sorts of random information.”

“Once they are all gathered I print them out and cut them up and then find their geographical location and divide them into boxes,” he said.

He has, for example, one box for the north of a city, one for the south etc. He then starts work on one area, sifting and editing through the information that he has gathered before, drawing as many of them on the map as possible.

When he has finished a section, he covers it up with A3 paper so that he can work on a new section without smudging the pencil with his elbows.

With fictional places such as Nova Utopia, he takes a slightly different approach. He started by reading Thomas More’s book Utopia and “started to pick holes in it.” “It plays around with the idea of utopias and dystopias,” he says. “Under the backstory of a capitalist revolution in 1900 on the island, everything has been privatized. Before there was no currency on the island—land ownership was a cardinal sin. Now everybody uses Utopia as a leisure island—a place where they can buy up land and build their own private utopias.”

He has placed the piece in a “hagioscope frame.” This fully encapsulates the work, allowing it to be visible only through a single, moveable portal fitted with a magnifying lens. This means that only one person can view the map at a time—an exclusive experience that is “making a mockery” of the egalitarian principles on which the traditional idea for Utopia is based.

“I like viewing works that require in-depth visual investigation. This forces you to look very closely at the picture.”

While his maps may have attracted a lot of attention, he doesn’t want to be known “just as a map man”. He says: “I love doing the maps and it’s a big chunk of my work but the landscape work is less didactic and I feel more like an artist.” One of his favourite landscapes is called Leyman, based on a landscape he saw in Dorset.

You can check out Walter’s work, presented by Tag Fine Arts, from July 3-28, 2013, at LondoNewcastle Project Space.

This story originally appeared on Wired UK.