By Joseph Alessio from SmashingMagazine.com:

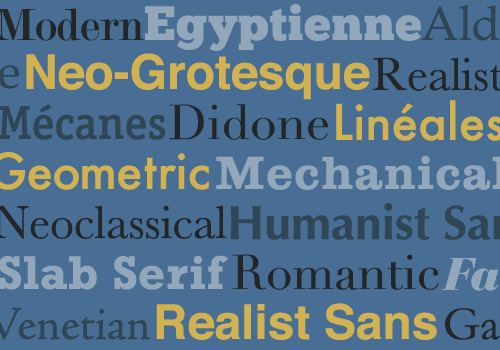

In the first installment of this two-part series on type classification, we covered the basics of type classification — the various methods people have used, why they are helpful, and a brief survey of type history, classifying and identifying typefaces along the way. Unfortunately, we only got as far as Roman (traditional serif) typefaces and the early-19th century. Now we’re back for part 2!

Part 2 will primarily cover sans typefaces, with a nod to display typefaces and other less common categories, as well as address a few of the questions people have about whether type classification is helpful and necessary.

If you haven’t read part 1, now’s your chance to go over it. It lays important groundwork for this article, covers the categories of serif typefaces, and contains plenty of useful information about the development of serif type. If you already have read it, here is a quick recap to get us started before we move on to the new material.

Review

Type Classification Systems

Type has been classified in many ways over the years, both formal and informal — Thibaudeau, Vox, British Standards, etc. None of these are complete or all-encompassing, but they’re helpful as an aid to study as well as for learning to use type correctly and effectively. The material in this two-part series draws heavily from the Vox-ATypI system, which is the most “official” of the systems today, having been adopted by the Association Typographique Internationale in 1962 and still the most commonly referenced system.

Is it perfect? No, but it provides a good overview of what is out there; and when you describe typefaces using the terms you’ll learn in this series, anyone who is reasonably familiar with typography will know what you’re talking about.

Here is a quick overview of the type categories we covered in part 1.

Humanist/Venetian

- Notable calligraphic influence, patterned after handwriting.

- Strongly angled axis or stress.

- Based on typefaces designed in Renaissance cultural hubs such as Venice.

Garalde

- Less calligraphic influence because type began to be viewed as separate from writing.

- Named after influential type designers Claude Garamont and Aldus Manutius.

- Still has a tilted axis but less obvious than in Humanist type.

Transitional/Neoclassical

- No calligraphic influence. Designed independently, sometimes on a grid.

- First appeared in the late-17th century.

- Virtually vertical axis and high contrast between heavy and thin strokes.

Didone

- Extreme contrast between thick and thin. Rigidly vertical axis.

- Abrupt, or unbracketed, serifs. Very precisely designed.

- Named after Firmin Didot and Giambattista Bodoni.

Slab Serif

- Very heavy weight and low contrast between thick and thin.

- Unbracketed, prominent serifs.

- First typefaces created expressly for display purposes.